Why careers and employability learning matters in higher education

A summary of the evidence supporting quality careers and employability learning

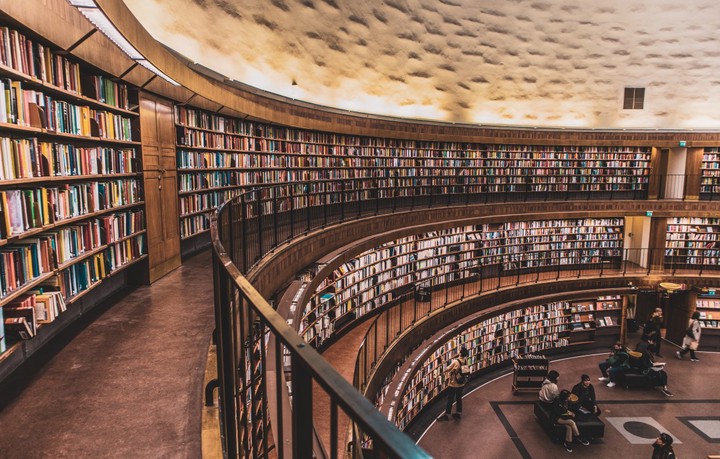

Photo by Anna Hunko on Unsplash

Photo by Anna Hunko on UnsplashThis article was originally published on LinkedIn. It is a summary of some of the key research that supports the important role that careers and employability learn plays in higher education.

About three years ago I wrote an article summarising my research into the evidence base of and best practices in careers and employability learning. I was pleased to see the warm response it got from my peers. Career development educators appreciated how I provided them with a clear, evidence-based argument of the contribution they make to their clients’ education and careers. Many have drawn on that evidence as they prepare proposals, report on their work, and in some cases, justify their roles.

Since then, I have continued to advocate for the value of career development theory, evidence, and practice. In this article I will share a little more of what I’ve learned from the literature about how university students benefit from quality higher education careers and employability learning.

What careers and employability learning can do for students

Several meta-analytic studies of career development interventions have shown that quality careers and employability learning has a positive impact on clients’ career decision making self efficacy, decidedness, career maturity, career adaptability, and sense of vocational identity, among other things (Langher et al., 2018; Ozlem, 2019; Whiston et al., 2017).

Studies which evaluate careers and employability courses for university students have found positive impacts on both career and academic outcomes, including adjustment to university, retention, completion, and achievement (Clayton et al., 2019; Hansen & Pederson, 2012; Reardon & Fiore, 2014; Reardon et al., 2015).

Research into job search skills and success has shown that interventions designed to teach people how to search and apply for jobs significantly increase clients’ self-efficacy and employment outcomes (Liu et al., 2014). Other meta-analytic research has demonstrated the importance of job search self-efficacy in achieving successful outcomes (van Hooft et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2019). Crucially, the clarity of a person’s goals and the quality of their job search, both of which are stock in trade for career development educators, predict not only job search success, but also the quality of the employment they secure (van Hooft et al., 2020).

Finally, research has shown that targeted education can improve entrepreneurial self-efficacy, intentions, and attitudes (Nabi et al., 2017) and networking behaviours and connections (Brown et al., 2019; Jokisaari & Vuori, 2011; Spurk et al., 2015), both of which contribute to university students’ career success.

What quality careers and employability learning looks like

I’ve written before on the career education evidence base, my curricular vision for careers and employability learning, and in particular, dialogical approaches that hold a lot of promise. In summary, there is support for the effectiveness of:

- repeated interventions, facilitated by a career development expert, delivered to groups (Brown & Ryan Krane, 2000; Whiston et al., 2017)

- targeting specific student needs and applying appropriate theories in a rigorous fashion (Langher et al., 2018; Whiston & James, 2013)

- certain critical ingredients of career interventions: written exercises, individual feedback, a strong working alliance between educator and student, labour market information and world of work exploration, mentoring and social support, values clarification, and psychoeducation (Brown & Ryan Krane, 2000; Langher et al., 2018; Whiston et al., 2017)

In addition, it’s important to note an approach that is not currently supported by any evidence: computer based interventions without the moderation of a career development educator (Whiston et al., 2017).

How to use this body of evidence

The evidence is clear: the work of career development educators has a positive impact on student outcomes. These citations can certainly support any argument you put forward to advocate for the role of career development education at your university. But by themselves, they are not enough.

In my experience, the academics and executives that career development educators find themselves trying to convince are not going to be swayed by a few research papers. What they want to know is how your programs and services improve the outcomes of their students. So it’s vital that you draw on this existing research to design your own rigorous evaluations, rather than just sprinkle a few citations through your proposals and reports.

You need to show that your professional expertise has a real and measurable impact on the students you work with. Assess the outcomes of your programs with valid and reliable measures. Collect stories about student experiences of your programs to enrich your measurements with qualitative data. Most importantly, be curious about how your decisions as an educator impact what the student learns.

We have an abundance of evidence here at our fingertips, but we need to learn how to better use it to design and evaluate high quality quality careers and employability support for our students.

References

Brown, J. L., Healy, M., Lexis, L., & Julien, B. (2019). Connectedness learning in the life sciences: LinkedIn as an assessment task for employability and career exploration. In R. Bridgstock & N. Tippet (Eds.), Higher Education and the Future of Graduate Employability: A Connectedness Learning Approach (pp. 100–119). Edward Elgar. doi.org/10.4337/9781788972611.00015

Brown, S. D., Ryan Krane, N. E., Brecheisen, J., Castelino, P., Budisin, I., Miller, M., & Edens, L. (2003). Critical ingredients of career choice interventions: More analyses and new hypotheses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(3), 411–428. doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00052-0

Clayton, K., Wessel, R. D., McAtee, J., & Knight, W. E. (2018). Key careers: Increasing retention and graduation rates with career interventions. Journal of Career Development, 46(4), 425–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845318763972

Goodwin, J. T., Goh, J., Verkoeyen, S., & Lithgow, K. (2019). Can students be taught to articulate employability skills? Education + Training. doi.org/10.1108/ET-08-2018-0186

Hansen, M., & Pedersen, J. (2012). An examination of the effects of career development courses on career decision-making self-efficacy, adjustment to college, learning integration, and academic success. Journal of The First-Year Experience & Students in Transition, 24(2), 33–61.

van Hooft, E. J., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Wanberg, C. R., Kanfer, R., & Basbug, G. (2020). Job search and employment success: A quantitative review and future research agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology. doi.org/10.1037/apl0000675

Jokisaari, M., & Vuori, J. (2011). Effects of a group intervention on the career network ties of Finnish adolescents. Journal of Career Development, 38(5), 351–368. doi.org/10.1177/0894845310376174

Kim, J. G., Kim, H. J., & Lee, K.-H. (2019). Understanding behavioral job search self-efficacy through the social cognitive lens: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Vocational Behavior. doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.01.004

Langher, V., Nannini, V., & Caputo, A. (2018). What do university or graduate students need to make the cut? A meta-analysis on career intervention effectiveness. Educational Cultural and Psychological Studies, 17, 1. doi.org/10.7358/ecps-2018-017-lang

Liu, S., Huang, J. L., & Wang, M. (2014). Effectiveness of job search interventions: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1009–1041. doi.org/10.1037/a0035923

Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 277–299. doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0026

Ozlem, U.-K. (2019). The effects of career interventions on university students’ levels of career decision-making self-efficacy: A meta-analytic review. Australian Journal of Career Development, 28(3), 223–233. doi.org/10.1177/1038416219857567

Reardon, R. C., & Fiore, E. (2014). The effects of college career courses on learner outputs and outcomes, 1979-2014: Technical report No. 55 (p. 48). The Center for the Study of Technology in Counseling and Career Development, Florida State University.

Reardon, R. C., Melvin, B., McClain, M.-C., Peterson, G. W., & Bowman, W. J. (2015). The career course as a factor in college graduation. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 17(3), 336–350. doi.org/10.1177/1521025115575913

Ruschoff, B., Salmela-Aro, K., Kowalewski, T., Kornelis Dijkstra, J., & Veenstra, R. (2018). Peer networks in the school-to-work transition. Career Development International. doi.org/10.1108/CDI-02-2018-0052

Spurk, D., Kauffeld, S., Barthauer, L., & Heinemann, N. S. R. (2015). Fostering networking behavior, career planning and optimism, and subjective career success: An intervention study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 134–144. doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.12.007

Whiston, S. C., & James, B. N. (2013). Promotion of career choices. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 565–594). Wiley.